How The FDA, MHRA, & EMA Differ On Externally Controlled Trials

By Dan Schell, Chief Editor, Clinical Leader

Back in August, I wrote that I had become a little obsessed with understanding synthetic and external control arms.

Bad news … I still haven’t gotten this topic out of my system.

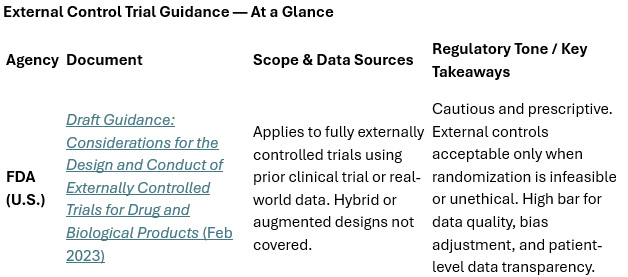

The good news is, I’m focused on the regulatory aspect of this topic for this article. After all, when the FDA introduced its draft guidance on externally controlled trials in 2023, it marked a turning point: Regulators were finally beginning to formalize expectations for what had long been a gray area in trial design. External control arms — using data from outside the randomized trial, often from prior studies or real-world sources (e.g., RWE) — were gaining traction as a way to fill evidence gaps, especially in rare or rapidly progressing diseases. But as sponsors quickly discovered, enthusiasm outpaced regulation.

Now, with the U.K.’s MHRA and the EU’s EMA joining the discussion, the global rulebook is taking shape. While all three agencies share a commitment to scientific rigor and patient safety, they diverge sharply in scope and tone, which leaves sponsors to navigate a patchwork of expectations when a concurrent randomized control isn’t feasible.

The FDA: Open, But Not Overly Welcoming

The FDA’s guidance remains the most mature and detailed of the three, and it doesn’t mince words about the risks. It warns that “in many situations, the likelihood of credibly demonstrating effectiveness … with an external control is low,” mainly because of unmeasured confounding and data inconsistencies. Still, it acknowledges that in some situations — rare diseases, life-threatening conditions, or trials where randomization would be unethical — external controls can serve as a legitimate evidentiary bridge.

The guidance emphasizes several key requirements:

- patient-level data rather than summary statistics

- pre-specification of inclusion criteria

- statistical techniques to adjust for bias

Sponsors are expected to engage early, justify why a randomized control isn’t viable, and show how comparability between cohorts will be ensured. In essence, FDA’s message is: Use external controls only when you must, and be ready to defend every analytic choice.

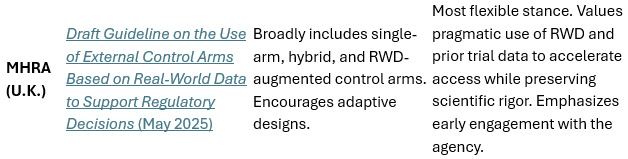

The MHRA: Broad, Flexible, and Pragmatic

Across the Atlantic, the MHRA Draft Guideline on the Use of External Control Arms Based on Real-World Data to Support Regulatory Decisions (May 2025) takes a notably more progressive stance. While rooted in RWD, the MHRA’s definition encompasses both fully external single-arm studies and “augmented” designs that blend internal and external control groups.

I believe this broader lens matters. By explicitly welcoming hybrid designs, MHRA acknowledges what trialists already know: Ethical, logistical, and feasibility constraints often demand flexibility. The agency even notes that randomized trials with internal controls “augmented with external controls” are generally preferred to single-arm trials — but it doesn’t dismiss the latter. Instead, it encourages adaptive designs that can recalibrate as data mature.

That kind of realistic (no pun intended) approach to using RWD and external control trials was refreshing to me. MHRA’s guidance reflects a regulator trying to meet sponsors halfway — encouraging innovation while still prioritizing scientific credibility. The tone is pragmatic, suggesting that a positive regulatory decision can be reached “If the data are sufficiently convincing,” even when a more traditional randomized design might have been ideal.

For U.K. sponsors and multinational programs that include U.K. sites, this approach provides a clearer path for using historical trial data, disease registries, or routinely collected RWD to strengthen submissions. It also positions MHRA as the most flexible of the three major regulators — a potential advantage as global sponsors look for efficient pathways that don’t compromise rigor.

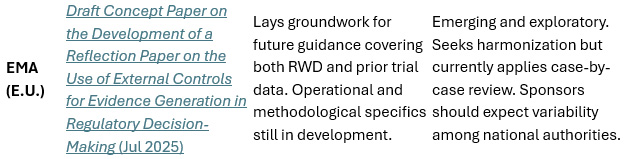

The EMA: Late to the Table, But Listening

The European Medicines Agency’s Draft Concept Paper on the Development of a Reflection Paper on the Use of External Controls for Evidence Generation in Regulatory Decision-Making (July 2025) signals that Europe is still in exploration mode. Rather than a full guideline, it’s a precursor — a framework describing what the forthcoming reflection paper should address.

The concept paper admits that “a standard definition of external controls is currently not available,” underscoring how fragmented the European landscape remains. Still, the EMA recognizes the growing demand for clarity and the need to integrate external controls into its broader real-world evidence roadmap. The planned reflection paper will tackle operational feasibility, methodological rigor, and statistical design — areas sponsors have long struggled to interpret across EU member states.

For now, however, the absence of concrete guidance means variability. What passes muster with one national authority may not with another. Sponsors filing in Europe must assume more regulatory back-and-forth, more requests for justification, and potentially longer timelines. Yet the agency’s inclusion of both real-world and prior clinical-trial data in its planned framework hints that it may ultimately align more closely with MHRA’s flexible philosophy than FDA’s more rigid definitions.

Where the Lines Converge — and Don’t

Despite stylistic and structural differences, the three regulators are converging on several key principles. All insist that external controls should be used only when randomized controls are impractical or unethical. All require sponsors to demonstrate comparability between populations, ensure transparency in data provenance, and apply bias-mitigation techniques robust enough to withstand regulatory scrutiny.

Where they diverge is in their comfort level with innovation. FDA is cautious and methodical; MHRA is more open to creative, blended approaches; EMA is somewhere in the middle — receptive but still formulating the rules. This divergence matters. For global sponsors and CROs, inconsistent expectations can translate into duplicated work, conflicting analyses, and months of additional regulatory negotiation.

As the Clinical Research Data Sharing Alliance (CRDSA) noted in its October 2025 white paper, “Sponsors are left to reconcile contrasting, and sometimes conflicting, guidance,” a problem that slows drug development and delays patient access.

The Takeaway for Trial Planners

For sponsors and CROs considering external controls, the operational implications are clear:

- engage regulators early

- document everything

- assume skepticism

These designs can reduce patient burden and accelerate timelines, but they demand extraordinary transparency. Data sources must be traceable, analytic methods reproducible, and confounding factors addressed head-on.

Used judiciously, external controls can transform evidence generation — especially in rare disease, pediatric, or oncology programs where conventional randomization isn’t realistic. But used carelessly, they’re a fast track to regulatory rejection.

Until global regulators harmonize their approaches, sponsors will need to design studies that can flex between agencies, satisfying FDA’s rigor, MHRA’s pragmatism, and EMA’s evolving expectations. That’s not easy — but guess what — that’s the reality of modern evidence generation. In an era where data move faster than policy, the smartest trial designers won’t wait for consensus; they’ll build it into their protocols from the start.